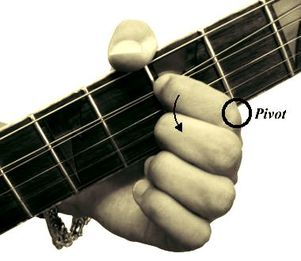

Harmonized scales/melodies are a great technique many bands like the Eagles, Pink Floyd and the Allman Brothers use to great effect. Initially, I like to teach this concept predicated on the major generated modes, which are: Ionian, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian and Locrian. The first step is to learn those scales... Once you've done that, I recommend you use either a loop pedal or recording software to do the following: First, record yourself playing a G major scales (up and back ) then, when you play it back, play a B phrygian scale over it, then do the same with a C Lydian scale and a D Mixolydian scale. These three harmonies, 3rds, 4ths and 5ths will sound the most familiar but still really interesting. Next, let's harmonize a simple, diatonic melody: well go really simple here and use “Ode to Joy”. Play the first part of the melody in the G major scale shape, the notes are: B – B -C D – D – C- B – A – G – G -A – B – B – A – A. If you convert the intervals of the melody into scale degrees, you have: 3 – 3 - 4 – 5 – 5 – 4 – 3 – 2 – 1 – 1 -2 – 3 – 3 – 2 – 2. (Which, in this example are both the scale degrees AND the intervals, this will not be the case with the harmonized scales) Now, to harmonize the melody notes from the G major scale in either 3rds, 4th or 5ths simply use the same scale degrees in the harmony scale as you did in the original melody played within the G major scale. Ex) To harmonize in 3rds, use the B Phyrgian scale and the degrees are the same as in the G major based melody – the B is harmonized with the D and the C is harmonized with the E etc.  This blog isn't about the annoying tactic politicians use to avoid answering tough questions but is about an exciting musical technique I'll explain how to use! I teach this technique to all my students. It has a classical-ish sound I think you'll like. In addition to sounding great, learning this technique will also greatly help your picking and left hand dexterity along with helping you become very familiar with scales and tonalities. The formula for pivoting within a scale is very simple: begin on the root of any scale and instead of playing the scale in order ascending (ex: C - D – E – F – G – A – B ) after each subsequent note, return to the root note = C – D – C – E – C – F – C – G – C – A – C – B. This technique works with every scale. Once you've gotten comfortably with the concept you can then apply the same idea but descending from the root = C – B – C - A – C – G – C – F – C – E – C – D Finally, another application for pivoting is to use the 3rd or 5th as the pivot note that you return to. For example, if you're pivoting in a C major scale, play: E – D – E – C – B – E – A – E – G – E – F (descending pivot off of the third of the scale) Pivoting is a great technique to add to your improvisational repertoire and for writing guitar or bass parts/lines – I particularly like to mix pivoting with arpeggios, the amount of variety and interest that can create is endless. Becoming a competent, well rounded musician is hard work and truly meritocratic in the sense that if you hear a great musician there is a 100% chance that they have put in thousands of hours of practice in an efficient and focused manner. Part and parcel of that is developing good habits and approaches to all the component parts of playing your instrument.

Here's a list of several such habits and approaches, the more you adhere to these, the more you'll progress and maximize your potential:

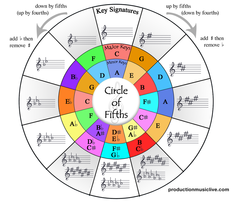

A chord inversion is when another note in a chord in played in the bass. If a chord has 3 notes (triad) there are 2 possible inversions – the 3rd in the bass is called the first inversion and the 5th in the bass is called the second inversion. If a chord has 4 notes (4 part harmony) there are 3 possible inversions – the first and second inversions are the 3rd and 5th in the bass respectively (just like the triads) and the third inversion is the 7th in the bass When I teach inversions I have my students practice every permutation of inversions in their progressions. This can create interesting bass movement and add a lot to your playing. In the next blog I'll explore several specific ways of doing this. Another way to utilize inversions is: when you're playing a chord for say two measures, a measure or two beats you could play, respectively, a measure on a chord and a measure on one of it's inversions, two beats on a chord and two beats on one of it's inversions or one beat on a chord and one beat on one of it's inversions. Lastly, you should also practice cycling through inversions, for ex) play a Cmaj7 for two beats then it's first inversion (Cmaj7/E) for two beats then it's second inversion (Cmaj7/G) for two beats and finally it's third inversion (Cmaj7/B) for two beats and do this process for every chord.  Now that you know how to calculate the number of accidentals in each key, the next step is to learn which notes are sharp of flat). There's a concept called the “order of flats” and it's inversion, the “order of sharps”, there are the specific sequence of flats and sharps the occur in the keys (the right hemisphere uses sharps and the left uses flats). To calculate the order of flats, simply start at 5 o'clock and proceed counter-clockwise through 11 o'clock = B – E -A – D – G – C – F and conversely and conveniently, the order of sharps is the reverse of the order of flats: 11 o'clock proceeding clockwise through 5 o'clock = F – C -G -D -A -E – B. Thus far, we've only be discussing major keys, there are also 12 minor keys encapsulated in the circle of fifths (these minor keys are relative to the major keys) To calculate them begin with Am at 12 o'clock and proceed clockwise in 5ths =Am – Em – Bm – F#m – C#m – G#m. Then proceed counter-clockwise in 4ths = Am – Dm – Gm – Cm – Fm – Bflatm – Eflatm. |

AuthorEric Hankinson Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

|

The Chromatic Watch Company

(my other business) |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed