It's useful to think of relative major and minors as the same notes or chords but with different starting and end points. For example, C major and A minor are reciprocal relatives to each other, both key have the same notes and chords, in this case, all natural notes. A C major scale is C through C natural and an A minor scale is A through A natural, the same notes but with different starting and end points. It's also useful to learn to identify the relative minor key and scale contained within the major key and scale and the reverse. (the major key and scale contained within the minor key and scale) If you play a two octave C major scale for example, the A minor scale is the same notes beginning on the sixth degree of the scale and going past the octave to the thirteenth and if you play an A minor scale in two octaves, the C major scale is the same notes but beginning on the third degree of the A minor scale and going past the octave to the tenth scale degree.  The concept of relative major and minor keys and scales is very useful for understanding composition and improvisation. Relatives share the same notes. Every major key has a relative minor key and every minor key has a relative major key. Every major scale has a relative minor scale and every minor scale has a relative major scale. Here is a simple formula you can use to calculate the relatives: If you're in a major key or scale to find the relative minor simply move a minor 3rd lower (three half steps) which on the guitar or bass is 3 frets lower (to the left) for example, C is at the eight fret of the E string, if you're in the key of C major to find it's relative minor, move three frets lower which is A. A minor is the relative minor of C major, this applies to both the key and the scale. The keys and scales of C major and A minor contain the same notes, in this case, all natural notes. Conversely, if you're in a minor key or scale, to calculate it's relative major, move up a minor 3rd. If you're in A minor, move up three frets and that gives you a C, C major in the relative major to A minor. To reiterate in simple terms: major to relative minor = up a minor 3rd and minor to relative major = down a minor 3rd. Tune in next week for Part 2 of this series... .Secondary dominant chords are a series of six chords you can use to substitute for or augment the seven diatonic chords in major and minor keys.

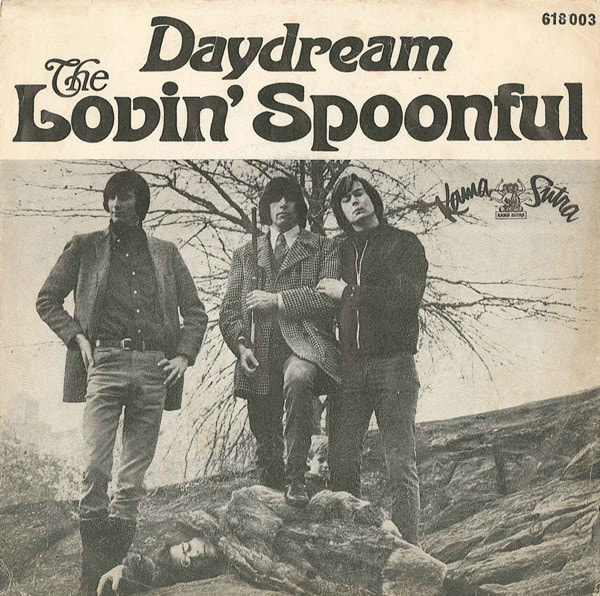

There is a very simple formula you can use to calculate the secondary dominant chords to all chords in keys. (all chords except for the diminished chord) You simply count up a fifth from the root of each chord and you'll get the secondary dominant chord of each of the diatonic chords. For example, we'll use the key of C, the one chord is C major, if you count up five steps above C you get a G note, then you make a dominant chord based on that root and you get a G7 chord, G7 is the secondary dominant of C. Here are the remaining secondary dominants in the key of C: Dm=A7, Em=B7, F=C7, G=D7, Am=E7. Those secondary dominant chords can be used in conjunction with the diatonic chords in the key of C, which are: C, Dm, Em, F, G, Am and Bdim to write chord progressions. All six of the secondary dominant chords are commonly used in popular music and add a great deal of richness and harmonic interest to the seven diatonic chords. A well known example of secondary dominant chords in a song is “Daydream” by the Lovin' Spoonful, the verse is: G - E7 – Am7 – D7 (the E7 is a secondary dominant of the Am) and the bridge is: C – A7 – G – E7 (the A7 is the secondary dominant of the Dm). After many years of making multitrack recordings at home I'm convinced it's a totally worthwhile activity that will help make you a better overall musician.

The complexity of juggling so many musical variables at once, while very challenging will certainly take you to the next next level of musicianship. The rigors of working out each part in detail, getting the performances as tight as possible, deciding how to best get the sounds you want via instruments, effects and amps will hone your attention span which will help generally, your musicianship. The best players put in the most time AND practice efficiently while constantly learning new material and pushing themselves. Additional benefits to multitrack recording are that you'll become a better and more critical listener and your musical abilities will improve from the demands of mixing parts, editing the EQ, panning, harmonizing, experimenting with rhythm and more. Finally, another benefit/side effect you may not have thought of which is fairly common is, after some time of making recordings of yourself, you may develop the desire to learn a new instrument or two to spice up your songs! Want to learn more? Get in touch and let's chat... Part 3 in my Guitar Keys series (see part 1 here and part 2 here)

This blog is going to cover the basics of major keys - what is commonly referred to as the "diatonic" major key. ("diatonic" means consistent with the scale the key is based on) In other words, in a diatonic major key, every note of every chord will conform to the notes of the major scale of the same root. For example, the C major scale is the only major scale with no sharps or flats (accidentals) and consequently, all seven diatonic chords in the key of C major consist of only natural notes. Some examples of famous songs in major keys are: "Hey Jude", "Sweet Home Alabama", "Beast of Burden" and "Brown Eyed Girl". Here's a simple process you can use to calculate the seven diatonic chords in all twelve major keys: 1. Pick the key you want to play in. 2. write out the major scale of that key. 3. plug in the following chord quality formula: ("quality" means the suffix of a chord: major, minor, diminished, augmented etc.) major, minor, minor, major, major, minor, diminished Example: C major scale= C - D - E - F - G - A - B diatonic chords in the key of C= C major, D minor, E minor, F major, G major, A minor and B diminished. |

AuthorEric Hankinson Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

|

The Chromatic Watch Company

(my other business) |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed