|

In a previous blog I explained Minor Keys, this will be an addendum to that content...

We'll begin by comparing the two scales that the chords of minor (natural minor) and harmonic minor are predicated on: The only difference between the two scales is that the harmonic minor has a natural 7th whereas the natural minor (minor) has a flat 7th. In the Key of Am, the minor scale is all natural notes (A – G) and in the harmonic minor scale, all notes are natural except for the 7th degree which, in this case would be a G# note. (A harmonic minor scale = A – B – C – D – E – F – G#) Here are the 7 chords built from the harmonic minor scale in the key of Am:

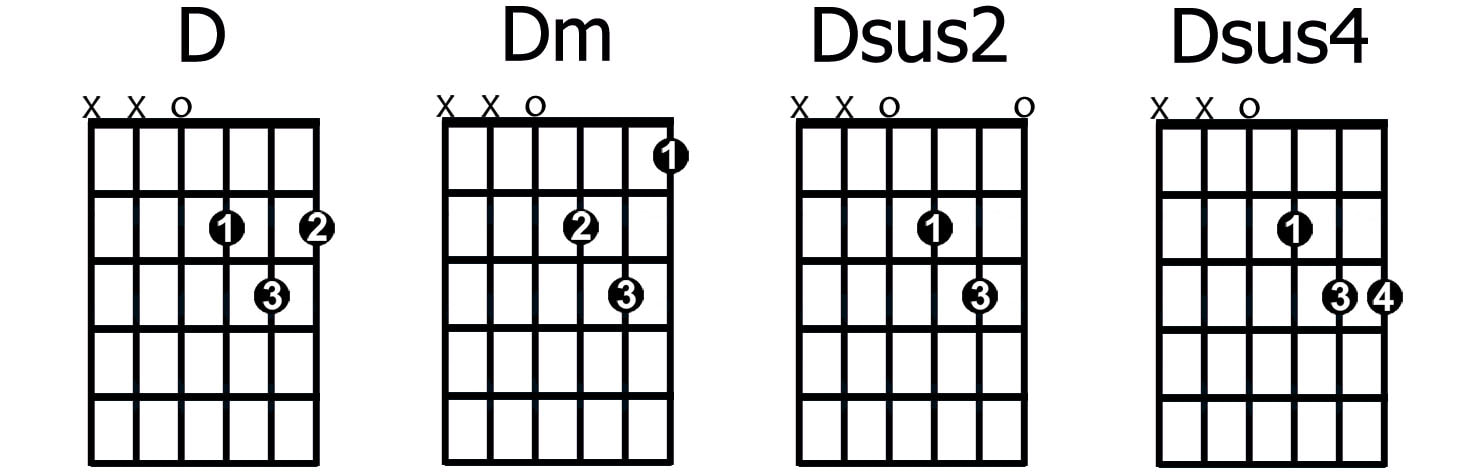

Even though the only difference between the scales of A minor and A harmonic minor is the G# note in the later, there are three differences in the chords generated by the harmonic minor as compared to the minor. In harmonic minor, you get two diminished chords and one augmented and in diatonic minor keys you get one diminished chord and no augmented chords. Also in harmonic minor, the V chord is major instead of minor which is a stronger cadence back to the tonic. Best of all, you can mix and match between the chords of minor and harmonic minor, which gives infinitely more options for interesting progressions. In the next blog I'll give examples of chord progressions using harmonic minor and ones that mix and match with both harmonic and natural minor. And finally I'll also show how to augment your songwriting options with a few tricks using chord borrowing and substitutions.  There are several approaches/tricks you can use to figure out chord progressions by ear... Your ear can most easily discern the highest and lowest notes in a chord. ( it's considerably more difficult to pick out the interior notes in a chord ) If your ear is already decent, try the following method: try and isolate the bass notes of each chord in the progression – often times when you find a bass note that “works” ( meaning that it sounds good played over the chord ) but proves to be incorrect, that note is a different chord tone, usually the 3rd or 5th ) Music theory knowledge is a big aid in this process in multiple ways. A jumping off point is knowing the diatonic chords in major and minor keys. Probabilistically thinking, the simpler/more conventional a song is, the more likely it is to contain diatonic chords. In other words, a powerful tool for figuring out chord progressions is a process of elimination. When you find a bass note that works then plug in the chord quality of the scale degree of that bass note, if the chord sounds incorrect the bass note might be a chord tone of a different chord. For ex) If the first chord in a progression is F and the second bass note is G but when you play a Gm chord it sounds wrong, ask yourself “what chord has G as a 3rd, and 5th , one of those may be the actual root. In this case G is the 3rd of E flat or the flat of Em or the 5th of C. The melody note ( highest note of a chord ), if discerned can guide you to correct chord often too. If you identify a melody note, first check if it's a chord tone. For ex) if you identify an A note, it might be the root or an A or the 3rd of an F or the flat 3rd of the 5th of a D. Watch this space, as my next blog will expound on this concept...  A chord inversion is when another note in a chord in played in the bass. If a chord has 3 notes (triad) there are 2 possible inversions – the 3rd in the bass is called the first inversion and the 5th in the bass is called the second inversion. If a chord has 4 notes (4 part harmony) there are 3 possible inversions – the first and second inversions are the 3rd and 5th in the bass respectively (just like the triads) and the third inversion is the 7th in the bass When I teach inversions I have my students practice every permutation of inversions in their progressions. This can create interesting bass movement and add a lot to your playing. In the next blog I'll explore several specific ways of doing this. Another way to utilize inversions is: when you're playing a chord for say two measures, a measure or two beats you could play, respectively, a measure on a chord and a measure on one of it's inversions, two beats on a chord and two beats on one of it's inversions or one beat on a chord and one beat on one of it's inversions. Lastly, you should also practice cycling through inversions, for ex) play a Cmaj7 for two beats then it's first inversion (Cmaj7/E) for two beats then it's second inversion (Cmaj7/G) for two beats and finally it's third inversion (Cmaj7/B) for two beats and do this process for every chord. Often when you hear a guitar player strumming some chords and you notice some motion going on within the chord that sounds nice and interesting – frequently, what they're playing are called “suspended chords” (or sus chords) Suspensions or suspended chords come in two varities – sus4 chords and sus2 chords. A suspended chord substitutes either the 4th or the 2nd in place of the 3rd. Ex) Csus4 = C – F – G and Csus2 = C – D – G. If you're playing a sus4 chords, most musicians just call that it a sus chord (the sus4 is a given) and if you're playing a sus2 chord, you need to call it as such. An aspect of sus chords many musicians aren't aware of is the fact that you can suspend many chords, not just major. Here are some examples: C7sus = C – F – G – Bflat, C6sus = C – F – G – A, C9sus = C – F – G – Bflat – D, C7sus2 = C – D – G – Bflat. I suggest that you take every major and dominant chord you know and practice making them into both sus and sus2 chords. Also, remember you can often do two versions of each suspension by placing the 4ths and 2nds into different octaves. Generally, suspensions are useful whenever you're playing a chord for some length of time. Also, suspensions are frequently played withing single note, arpeggiated chords. A famous example is in the intro of the Boston song “More than a Feeling”. .Secondary dominant chords are a series of six chords you can use to substitute for or augment the seven diatonic chords in major and minor keys.

There is a very simple formula you can use to calculate the secondary dominant chords to all chords in keys. (all chords except for the diminished chord) You simply count up a fifth from the root of each chord and you'll get the secondary dominant chord of each of the diatonic chords. For example, we'll use the key of C, the one chord is C major, if you count up five steps above C you get a G note, then you make a dominant chord based on that root and you get a G7 chord, G7 is the secondary dominant of C. Here are the remaining secondary dominants in the key of C: Dm=A7, Em=B7, F=C7, G=D7, Am=E7. Those secondary dominant chords can be used in conjunction with the diatonic chords in the key of C, which are: C, Dm, Em, F, G, Am and Bdim to write chord progressions. All six of the secondary dominant chords are commonly used in popular music and add a great deal of richness and harmonic interest to the seven diatonic chords. A well known example of secondary dominant chords in a song is “Daydream” by the Lovin' Spoonful, the verse is: G - E7 – Am7 – D7 (the E7 is a secondary dominant of the Am) and the bridge is: C – A7 – G – E7 (the A7 is the secondary dominant of the Dm). |

AuthorEric Hankinson Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

|

The Chromatic Watch Company

(my other business) |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed