|

In a previous blog I explained Minor Keys, this will be an addendum to that content...

We'll begin by comparing the two scales that the chords of minor (natural minor) and harmonic minor are predicated on: The only difference between the two scales is that the harmonic minor has a natural 7th whereas the natural minor (minor) has a flat 7th. In the Key of Am, the minor scale is all natural notes (A – G) and in the harmonic minor scale, all notes are natural except for the 7th degree which, in this case would be a G# note. (A harmonic minor scale = A – B – C – D – E – F – G#) Here are the 7 chords built from the harmonic minor scale in the key of Am:

Even though the only difference between the scales of A minor and A harmonic minor is the G# note in the later, there are three differences in the chords generated by the harmonic minor as compared to the minor. In harmonic minor, you get two diminished chords and one augmented and in diatonic minor keys you get one diminished chord and no augmented chords. Also in harmonic minor, the V chord is major instead of minor which is a stronger cadence back to the tonic. Best of all, you can mix and match between the chords of minor and harmonic minor, which gives infinitely more options for interesting progressions. In the next blog I'll give examples of chord progressions using harmonic minor and ones that mix and match with both harmonic and natural minor. And finally I'll also show how to augment your songwriting options with a few tricks using chord borrowing and substitutions. This is a very simple, yet effective trick you can use to great effect, particularly while playing over blues changes. ( I – IV – V ) And yes, it's exactly what it sounds like – taking the 6 notes of the minor blues scale ( 1 - flat3 – 4 – flat5 – 5 – flat 7 ) and then adding the natural 3.

This creates an interesting, smooth, blurring effect over dominant chords because it highlights the major/minor juxtaposition that's one of the hallmarks of the blues. You should learn how to add the 3rd in multiple octaves to all 5 positions of the minor blues scale. Beginning with minor blues box 1, if, for example, you're in the key of A, you play the minor blues scale at fret 5. You'll add the 4th fret of the A string ( C# ) and then in the next octave add the C# on the G string at fret 6 and it's a simple as that. You can follow the I, IV and V chords with this scale as they go past and it works great over all three chords. You'll be amazed at how much the addition of one little note can enhance your playing! To familiarize your ear with the sound, I suggest you lay down a 12 bar I – IV – V blues on your looper pedal or play over a jam track in either G or A and first play the minor blues scale with the major 3rd rooted on the 6th string and follow the chords as the progress. Then once you're good at that, move the IV and V chord related scales up to the 5th string to consolidate the parameters of your scales. Finally a really cool thing you can do in several keys, especially G, A, C, D and E, is to augment this idea of playing minor blues scales with added 3rds with open strings. For example, if you're in the key of A, when you're on the I chord ( A7 ), all of the open strings work well as toggle notes. ( E is the 5th, A is the root, D is the 4th, G is the flat7th, B is the 9th ) Then on the IV chord ( D7 ) you have: E is the 9th, A is the 5th, D is the root, G is the 4th, B is the 6th and finally for the V chord ( E7 ) E is the root, A is the 4th, D is the flat7th, G is the minor 3rd and B is the 5th. It's well worth the time and effort to embrace this approach and add a new dimension to your blues improvisation! (Make sure you've read part 1 first...)

In this part, we'll look at several steps/approaches you can take to get better and quicker at deciphering chord progressions. First tip is to listen to the song you want to learn on HEADPHONES, preferably good quality headphones. This confers multiple advantages – generally, you can hear in finer detail and guitar parts are often panned in one speaker or the other, in that case you can remove the other side so that you can more clearly hear the guitar. Listen as focused as possible, without your guitar and with your eyes closed.

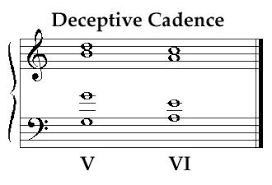

There are several approaches/tricks you can use to figure out chord progressions by ear... Your ear can most easily discern the highest and lowest notes in a chord. ( it's considerably more difficult to pick out the interior notes in a chord ) If your ear is already decent, try the following method: try and isolate the bass notes of each chord in the progression – often times when you find a bass note that “works” ( meaning that it sounds good played over the chord ) but proves to be incorrect, that note is a different chord tone, usually the 3rd or 5th ) Music theory knowledge is a big aid in this process in multiple ways. A jumping off point is knowing the diatonic chords in major and minor keys. Probabilistically thinking, the simpler/more conventional a song is, the more likely it is to contain diatonic chords. In other words, a powerful tool for figuring out chord progressions is a process of elimination. When you find a bass note that works then plug in the chord quality of the scale degree of that bass note, if the chord sounds incorrect the bass note might be a chord tone of a different chord. For ex) If the first chord in a progression is F and the second bass note is G but when you play a Gm chord it sounds wrong, ask yourself “what chord has G as a 3rd, and 5th , one of those may be the actual root. In this case G is the 3rd of E flat or the flat of Em or the 5th of C. The melody note ( highest note of a chord ), if discerned can guide you to correct chord often too. If you identify a melody note, first check if it's a chord tone. For ex) if you identify an A note, it might be the root or an A or the 3rd of an F or the flat 3rd of the 5th of a D. Watch this space, as my next blog will expound on this concept...  This blog is about a great songwriting tool that can be used to create interest and tension in chord progressions. For the purposes of this blog, we'll focus on adding a chord or chords between the cadence of V to I in multiple progressions. When a cadence doesn't bring you back to the 1 chord, that is called a deceptive cadence or delaying the tonic. Four common ways to delay the tonic are to instead go to either the vi chord, the IV chord, the iii chord or the ii chord following the V chord ( dominant ). (Additionally, the iii chord is a good substitute for the I chord because 2 out of 3 notes are common to both chords, for ex) if your I chord is C, the chord tones are: C – E – G and if you substitute a iii chord, the Em chord tones are: E – G – B, the only note not common to both is the C and B respectively ) This approach, of substituting the iii chord for the I chord is often done in the following progression: I – vi – ii – V in the key of A for example, ( played here as 4 part harmony chords ) are: A maj7 – F#m7 – Bm7 – E7 – C#m7 – F#m7 – Bm7 – E7. This alternating 4 stanza chord sequence is famously played in Gershwin's classic “I got rhythm.” Here are some examples: Instead of playing I – IV – V – I, play I – IV – V – vi or I – IV – V – IV ( in the key of C, those deceptive cadences would be: C – F – G – Am or C – F – G – F ). ii – V – I progressions are one of the most common chord progressions in western music, especially in jazz but really in most genres ( rock, folk, blues etc ) and they are a great context to use deceptive cadences too. Instead of playing ii – V – I, play ii – V – vi or ii – V – IV or you can extend the progression by tacking either the vi or the IV chords onto the end of the ii – V – I progression. Here are some examples in the key of G: Typical progression: I – ii – V – I Deceptive cadence: I – ii – V – iii – IV – V – I Typical progression: I – I in first inversion – IV – V – I ( G – G/B – C – D – G ) Deceptive cadence: I – I in first inversion – IV – V – ii7 – flat Iimay7 – G ( G – G/B – C – D – Am7 – Aflatmaj7 – G ). |

AuthorEric Hankinson Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

|

The Chromatic Watch Company

(my other business) |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed